The art of story

Published on 16 November 2023 by Andrew Owen (5 minutes)

As humans, the two main ways we learn are through play and story. When you’re trying to learn a new task, it’s often easier to learn by trial and error than by traditional instruction. It’s often said that mistakes and failures are the greatest teachers. But sometimes it’s better to learn from the experiences of others to avoid repeating their mistakes. Stories are important. They enable us to reach an audience not only beyond our own geography, but beyond our own lifespan.

The master of teaching story is Robert McKee. His books on the subject include “Story”, “Dialogue”, “Character” and “Action”. He has also co-written “Storynomics” a book on story-driven marketing in the post-advertising world. On the dust jacket to “Character” McKee is described as:

…a Fullbright Scholar, is the most sought after lecturer in the art of story. Over the last 30 years, he has mentored screenwriters, novelists, playwrights, poets, documentary makers, producers and directors. McKee alumni include over 60 Academy Award winners, 200 Academy Award nominees, 200 Emmy Award winners, 1,000 Emmy Award nominees, 100 Writers’ Guild of America Award winners and 50 Directors’ Guild of America winners.

This guy clearly knows his onions. But he doesn’t claim to have invented a new approach to storytelling. Rather he traces the ideas he teaches back to Aristotle’s “Poetics”. As an aside, I saw McKee give a lecture in Wellington, New Zealand. He agreed with me that bad writers love everything they write, and good writers hate everything they write. We hate it because we know it can always be better. But as I learned from working in newspapers, when the deadline comes you turn in what you’ve got and move on to the next thing.

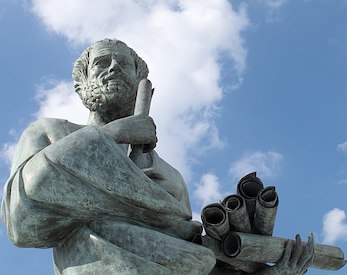

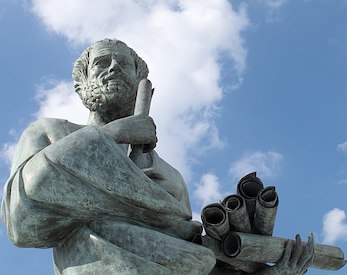

Poetics is the earliest surviving work of classical Greek dramatic theory. And half of it is missing. The section on comedy is lost. What we’re left with is the section on drama that mainly concerns tragedy. Aristotle identifies the various parts of tragedy in order of importance:

And although he’s talking about ancient Greek theater, he could equally be describing modern American film when he complains that these elements are usually prioritized in reverse order. Superhero films are particularly guilty of this, which is why after a while it’s hard to remember what distinguishes them besides the action set pieces and the soundtrack.

Thanks to Kent Beck, in software development we have the idea of the user story as used to describe the features of a system. For example:

As a <role> I can <capability>, so that <received benefit>.

The character is primarily defined by the role. But in telling a story, it helps to give the character depth. This can be seen in Fluid Topics’ “The terrible tale of Alice the tech writer”, It doesn’t just tell us the role of the protagonist, it tells us about her:

This is a great example of how story can help get your message across. In fiction, a commonly used model is the three-act structure. This breaks a story into the setup, the confrontation and the resolution. Each of the acts is composed of scenes with their own arc and story beats. This is the plot. In the Fluid Topics example, the setup is that Alice needs to update her company’s flagship medical diagnostic system installation and setup guide. The confrontation involves her trying to get the information she needs in time to get the manual out. The resolution is that she wings it and the manual is missing customer feedback and UI changes. But you can click the Fluid button to change the story to one that is less dramatic but with a happier outcome. The scenes are the headings “3 days and counting” and “7 days and counting”. The story beats are the time stamped events.

Thought and dialogue are somewhat interchangeable. They convey the inner narrative of the characters. For example: “Alice would like to improve the manual.” Characters must be true to themselves in thought and deed. We’ve already established that Alice is the kind of person who wants to do a good job. If we tell the audience that when she can’t get the feedback she needs, she decides to spend the afternoon browsing social media, we lose them. So these must be driven by the character we have established.

Sound and spectacle are the least important, but they’re still important. If you’re giving an in-person presentation, good audio and a great slide deck matter. Just not as much as the story you’re trying to tell. People remember good stories. If you prioritize these elements, all they will remember is the “soundtrack” and the “action sequences”.

Hopefully I’ve sold you on the power of story to get your audience engaged and remember what you’re trying to communicate. But Aristotle provides another tool in “Rhetoric”, his treatise on the art of persuasion. I would argue that the most important lesson from this work is on establishing trust. If you want to go even deeper, I would recommend Wayne C. Booth’s “Rhetoric of Fiction”, but I normally only recommend that to budding novelists.

And finally a software recommendation. Although Causality is intended for screenwriters, I’ve found it to be an excellent tool for creating scripts for demos and presentations. It’s free for short works, and it currently includes a readability graph that can be useful in making sure your audience stays engaged. It’s available for Linux, macOS and Windows.