Retro spotlight: Hedy Lamarr and wireless networks

Published on 15 February 2024 by Andrew Owen (4 minutes)

I first heard the name Hedy Lamarr in Mel Brooks’ film “Blazing Saddles”. The next time was when as a student journalist in the early 1990s I was trying to interview Tom Lehrer, and he suggested I interview her instead. I should have listened to him. I could have got the scoop on how her 1942 patent with George Antheil for spread-spectrum radio contributed to technology that we rely on daily, including cell phones, Bluetooth, GPS and Wi-Fi.

You’ll note that I said contributed. Some write-ups I’ve seen imply that Lamarr invented GPS. But the technology also relies on satellite geodesy models for measuring the Earth that were developed by Gladys West. As an aside, Ada Lovelace doesn’t usually get the credit she deserves for seeing the potential of Charles Babbage’s Analytical Engine as a general purpose computer rather than a pure number cruncher. Although, she did get a programming language named after her.

Born Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler in Vienna in 1914 to parents of Galician and Hungarian Jewish descent, Lamarr is best known for her film career that stretched from 1930 to 1958. She was in charge of her own destiny. At the age of 16, she forged a note from her mother to get hired as a script girl. At 23 she walked out on her marriage of four years and fled to Paris, allegedly while wearing all her jewelry. Later that year in London she turned down a $125 a week contract from Louis B. Mayer, booked herself on the same ship he was returning to New York on and secured a $500 a week contract by the time it docked.

On arrival in Hollywood, Mayer suggested she change her name to distance herself from her role in the then controversial “Ekstase” (Meyer’s wife was a fan of Barbara La Marr). But although she was successful, she wasn’t a party goer and was soon bored. So she turned to invention, an interest she developed as a child on walks with her father, who would explain how the devices they encountered worked.

“She doesn’t drink, and she doesn’t like parties… She’s a very bright woman, and… her idea of a good evening is a quiet dinner party with some intelligent friends. So she has to find some way to occupy her time. And what she does is take up, as a hobby, inventing. She sets aside one of the rooms in her house and puts up a drawing table and all the tools, the right kind of lights. There’s an entire wall of technical reference books on one side of the room. And she sets herself keeping busy in these off-hours, trying to come up with new ideas for inventions."—Richard Rhodes

For a more in-depth dive into Lamarr’s life there’s the 2012 book “Hedy’s Folly” by Pulitzer Prize winner Richard Rhodes and the award-winning 2017 film “Bombshell” written and directed by Alexandra Dean. The film includes an interview with Brooks who was named in Lamarr’s $10 million lawsuit against Warner Bros. over a character in Blazing Saddles named Hedley Lamarr.

“[The studio] said ‘This is ridiculous, we’ll go to court, we’ll fight it.’ And I said, ‘No! She’s beautiful. See if you can get a meeting.’ I read something about, you know, department store, embarrassment. ‘[I said]: ‘Give her within reason, pay her. Give her whatever she needs.’ You know, because, she’s given us so much wonderful cinematic pleasure for forty years. I think it’s incumbent on us to salute her is some, anyway we can. And send her my love and tell her where I live."—Mel Brooks

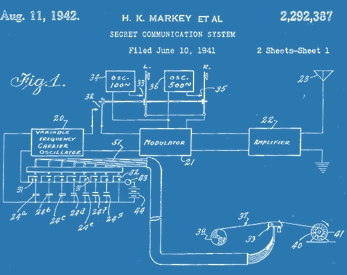

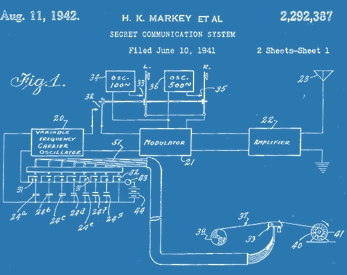

Her early inventions include an improved traffic signal and Kool-Aid-like cola tablet. During the Second World War, her attempt to join the National Inventors Council (NIC) was rebuked. Instead, she was persuaded to use her celebrity status to sell war bonds. But she carried on inventing. She had learned about torpedoes from her first husband, who was an arms dealer. She was horrified when in 1940 U-boats began targeting civilian ships. A torpedo guided using a single radio frequency could easily be jammed. This led Lamarr to the idea of frequency hopping. She discussed it with Antheil, a composer and pianist friend, who contributed the idea of using a piano roll to synchronize the frequency hops.

After the idea was submitted to NIC, Caltech professor Samuel Stuart Mackeown was brought in to consult on the electrical engineering. Lamarr hired LA law firm Lyon & Lyon to do a search for prior art, and she filed for patent under her legal name–Hedy Kiesler Markey. U.S. patent 2,292,387 was granted on August 11, 1942. But the US Navy didn’t get that the piano roll could be miniaturized, and sat on the idea until the patent expired. But in the 1950s it revisited the idea, and it began to be used in military communication. Lamarr’s work went unrecognized until in 1998 she was given a Communications Pioneer Freedom Foundation award. In 2014, Lamarr was posthumously inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame for frequency-hopping spread spectrum technology.