An introduction to intellectual property for developers

Published on 22 September 2022 by Andrew Owen (5 minutes)

This week, I’m going to take a brief look at intellectual property as it affects developers. It’s a vast topic, but the areas you’re most likely to come into contact with as a developer are copyright, trademarks and patents. Note that I’m not a lawyer and this isn’t legal advice. If you’re an employee, and you have any questions on intellectual property, consult your legal department.

I’ll start with trademarks, as they’re relatively simple. Broadly, there are two kinds: registered (®) and unregistered (™). A registered trademark is one that has been registered with an intellectual property office (IPO) in at least one jurisdiction for one or more classes of goods or services. It provides some protection from passing off (selling similar goods or services under a confusingly similar name) in the regions where it’s registered. An unregistered trademark is only enforceable in common law regions, provides a lesser degree of protection and requires more evidence of use.

You’ll probably only need to deal with trademarks in documentation. My advice is to have a section that lists them all and who owns them. Then there is no need to use the ® and ™ symbols in the main body of text.

Copyright applies to creative works, including software. It provides for a period of exclusive use, after which the work enters the public domain. Initially this was 14 years from the creation of the work, with the option to renew for up to 28 years. In US copyright law, it’s now 95 years from the date of creation for unattributed works, or 70 years after the death of the author. Where you create work as an employee, copyright resides with your employer.

Some contracts specify that your employer owns copyright on anything you create. If you create a podcast, they own it. If you have such a contract, and you create works on your own time using your own equipment, get your contract amended to remove any claims your employer has to any work you do that’s not directly related to your job function.

As a contractor, your contract should make it clear if the client will own the rights (work for hire), or if you’ll retain the rights and how they are licensed to the client. A contractor could license the same work to multiple clients. But as an employee, you can’t take any work you create with you if you change employer. So, with the basics out of the way, on to patents.

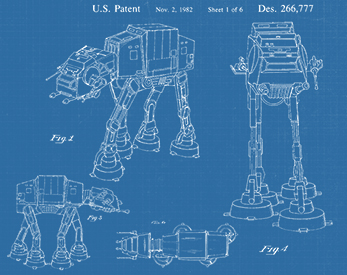

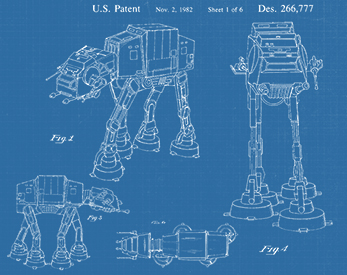

The UK IPO states that a patent “protects new inventions and covers how things work, what they do, how they do it, what they are made of and how they are made.” Patents give their owner “the right to prevent others from making, using, importing or selling the invention without permission.” Patent law varies by country, but the premise is the same. The inventor is given an exclusive right to profit from the invention for a limited period of time, 20 years in the case of the UK. But the invention is made public, and after the patent has expired, anyone else can use the invention without paying a royalty.

To receive a patent in the UK, an invention must “be new, have an inventive step that isn’t obvious to someone with knowledge or experience in the subject, and be capable of being made or used in some kind of industry.” In the past, software fell under the works that couldn’t be patented, together with scientific and mathematical discoveries and artistic works. But this is no longer the case: in 2004, software patents comprised 15 per cent of all patents issued in the US. The aim of the patent system is to encourage the disclosure of new discoveries. But, for developers, software patents can be a barrier to innovation.

One of the highest profile patent disputes of recent times was Apple vs Samsung. Both companies were close business partners, with Samsung acting as a major component supplier to Apple. In April 2011, Apple filed numerous claims against Samsung over design similarities between specific models of cell phones and tablets. Samsung counter-claimed that Apple had infringed on many of its related patents. The lawsuits were finally resolved in 2018.

The Samsung products ran Google’s Android operating system. In August 2011, Google acquired cell phone company Motorola Mobility for $12.5 billion, not for its products but for its portfolio of 17,000 patents and 7,500 pending patents. Google subsequently extended the protection afforded by those patents to all manufactures of Android devices, such as HTC.

In April 2010, Microsoft announced that it had reached a patent agreement with HTC. In practice, this meant that HTC had agreed to pay a royalty to Microsoft on every Android device it sold. It was never established if Android infringed on any of Microsoft’s patents, but HTC decided that it made better business sense to pay the royalty than risk action in the courts. These examples illustrate the difficulty companies face, both in protecting their own patents and in avoiding infringement of the patents of other companies.

Patents can give companies a commercial advantage in numerous ways. Android is open source software, but Google benefits from its tight integration with its services. In most markets the costs of searches, applications and enforcement make patents an option that only larger firms can afford. As a result, there are companies that exist solely to acquire patents with the intent of taking companies that can’t afford the legal fees to court (getting a payout if the company offers to settle). To counter this, companies may band together to form patent pools for their mutual protection from such claims.

But patents have their limitations. They can be renewed, but not indefinitely, and they have a much shorter term than copyright. There is no global agreement on patents. You can get EU-wide protection, but typically you have to file patent applications in many countries. The rules and standards vary widely. For example, prior publication is acceptable in the US, but in most other countries it’s not. As a result, enforcement can result in multiple legal cases in multiple jurisdictions.

Hopefully you won’t need to worry about intellectual property too often, but it’s worth being aware of it, if only to avoid exposing yourself to the risk of legal action.

Image: https://patents.google.com/patent/USD266777S/en